Sunday, March 11, 2007

contact

Dhanaraj Keezhara lives in Bangalore with his wife Nisha and son Siddhartha.

Contact address: 692, Masjed Street, Ramaswamy Palayam,

Maruthi Sevanagar, Bangalore, 560033, India.

Phone no: 080-25420188

E-mail: dhanarajkeezhara@rediffmail.com

about paintings

Truth from the margins

A myriad of ecosystems held in a delicate balance, sustaining the cultural imaginings of communities from time immemorial, threatened with destruction; urban dissonance and violence and an increasing human estrangement from nature- these are some concerns that have given impetus to Dhanaraj Keezhara’s work through the years. His vivid canvases continue to be melancholy yet arresting reminders of progressive human encroachments on the natural and a deep sense of loss of more consonant ways of living. Painting is at once a reaction and a response to urban life around him, organizing and reflecting on the incredible chaos one is constantly bombarded with as well as a concretization of hope and possibility. Different media excite him, allowing for different engagements and new modes of ex-pression. In his painting, sketching and sculpture one can discern a constant striving towards clarity of vision and an unfailing hope for a harmonious world.

Dhanaraj’ s work has been a continuous engagement with art-practice as emerging from the negotiations of people with their society and environment. Fired by a belief in art's ability to heal and renew a world torn asunder by violence and strife, he has continuously involved himself in community initiatives and education. From his student days at the College of Fine Arts, Kannur, through his ten year stint at various NGO’s and his present work at CHRISTEL HOUSE INDIA, art has always been a means of connecting with people and sharing his emotions and experiences. He has lived and worked with several indigenous communities including the tribal communities of Wayanad in Kerala, the Lambani community of Bidar, bordering Karnataka and Maharashtra as well as the Narmada valley community during the Narmada Bachao Andolan (Save Narmada Campaign). These experiences and dialogues continue to enrich his work.

His paintings dialogue with contemporary urban environmental discourses, harking back to non-urban modes of living as possible ways of reimagining human relationships with nature. The series Truth from the Margins gives ex-pression to experiences that emerged from the local Kannur community’s dialogues with the art form of Theyyam. One of the ritual art forms of North Kerala, in its nature worship, its obeisance to earth, air and water, ritual worship and shamanic performances, Theyyam is a festive reaffirmation of the organic relationship of humans to a natural world. Trees, animals and insects co-inhabit these canvases with tools and implements, contextualizing human activity within the productivity of nature. Fragments of fractured and disparate realities that the artist seeks to pull together, these vibrant explorations gesture towards a link between the everyday and the spectacular where the Theyyam experience manifests itself for the artist in the local mannerisms and postures of the people of the community.

Strongly figurative in their mode, these paintings draw on an almost elemental fluidity of shape and line to re-imagine and transfigure the natural world. Nature continues to be indicative of the human psychoscape and inner turmoil and outer disturbances draw on each other. In these canvases, melancholic human figures populate vividly colored and richly textured symbolic landscapes imparting to these works a ruminative and contemplative quality. Recent additions, while they continue the association of figure and motif that is such a strong feature of this series, give one the sense of being infused with light, imparting to these canvases a sense of lightness and hopefulness.

Much of Dhanaraj’s recent work continues to address contemporary concerns of the environment and the ecosystem, revisiting earlier explorations of the human relationship with nature and often launching into a critique of commercialism and dissonant living. Some paintings attempt a visualization of an idea of violence and disharmony. His series on contemporary contentions around water that seem to threaten into extinction older more harmonious relationships between the human and the natural world often take up this mode of depiction where they continually gesture towards the need for restoring society's connections with the natural world. The urban is constantly drawn on, albeit for the purposes of a critique. It is conceived as a site of dissonance and waste, and urban landscapes, symbolizing disharmony and clutter continue to act the foil for an imaginative exploration of possible harmony. And yet, interestingly urban dystopia becomes at once a site for artistic production as well the source of new metaphors for such a critical imagining.

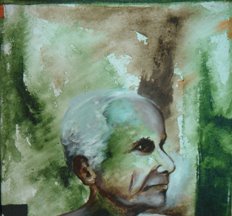

A recent painting, Cityscape brings together many of these concerns. Here an iconic colonial image is given a completely dramatic twist, reclaiming it for yet another imaging of dystopia. Deliberately provocative, the painting images an emaciated Gandhi figure with one hand resting on a rifle standing against the chaotic lines and angles of a cityscape. Is the Gandhi figure an impoverished icon or the everyman? Is this an ironic remark on what remains of Gandhism today? Communication remains for this artist the motivating force of painting and each of these canvases are like isolated impressions crystallized on canvas. And artistic ex-pression allows for a tapping and channelizing of an individual's inner creative energies to continue to attempt a dialogue between the extant and the possible

Many paintings take up another aspect of the consequences of war and violence: its effect on childhood and memory. Children are pictured as bearing the brunt of modern warfare and terrorism where they come to be caught in the crossfire. In his painting Dreamscape, the artist’s wonder at a fleeting impression of precocious child quietly asleep metamorphoses into this arresting image of childhood and fragile peace in dystopia. Like other recent canvases, it possesses a graphic clarity and starkness of image where single and distinct human figures float against dramatic landscapes dreaming, fleeing, seeking or simply remembering. An experience of loss remains central to these paintings –whether it is the loss of the rural, the loss of peace or the loss of childhood. Enigmatic and powerful, his painting Old man and the Hibiscus hovers between an impression of suffering and a recollection of youth long gone, in which the twin impulses of imaging a critique and envisioning a retrieval hang in a fragile balance.

Many of his paintings become commemorations of places, moments, and practices, rescuing them from a threatened oblivion. While the memory of a rural culture is encapsulated and coded in the smell of the white flowers that the Palamarapookkal seeks to evoke, a painting like the Mother Earth attempts a mapping of a sacred geography of myth and memory in its commemoration of the kavu which is seen as inviolable and sacred for the local community. In there paintings one is struck with the forceful attempts at preservation and perpetuation of a distinct cultural imagination. Simultaneously they also bring together the twin impulses of the evocation of loss and attempts at retrieval. This is typified in the painting Kurunjimala where the blooming of the flowers, a moment of indescribable beauty is inseparable from its associations in local myth as the harbinger of calamity and destruction. In these paintings one discerns a movement from the evocation of schisms and dissonance to a more complex evocation of destruction in beauty and perhaps their inseparability.

A strongly ethnographic impulse is at work in many of these attempts at retrieval where an almost photographic concern with the capturing of actual action and posture of the indigenous of Kerala is drawn into a visual reframing of that gesture within Dhanaraj’s vision. Whether it be the emphasis on the form of the indigenous figure or the unfailing association of implements with human figures, or again in the constant return to the gestural in cultural understandings, Dhanaraj’s enigmatically rehearses the attempt to connect with the experience of the culturally foreign, through a visual capturing of the gesture and the body language of the indigenous figure whose cultural essence lies encoded within and is constantly renewed through a daily unconscious re-enactment of a single gesture.

Themes of loss and retrievals of memory remain enduring concerns in Keezhara’s paintings. This preoccupation emerges in his painting as the absences in contemporary urban life but subsequently move on to an imagining of a cultural wholeness and a harmony with the natural. It also becomes Dhanaraj’s s way of articulating this experience of loss and seeking a renewal.

Thus his paintings are preoccupied with the idea of retrieval as they individually chart out the process of just such an attempt. And yet one might ask, are these paintings not themselves the only actualizations, the forging of those links and connections, the psycoscapes for the playing out of these imagined retrievals?

--- Sushmita Sridhar

New delhi

December 2006

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)